How Compose works

With Docker Compose you use a YAML configuration file, known as the Compose file, to configure your application’s services, and then you create and start all the services from your configuration with the Compose CLI.

The Compose file, or compose.yaml file, follows the rules provided by the

Compose Specification in how to define multi-container applications. This is the Docker Compose implementation of the formal Compose Specification.

Computing components of an application are defined as services. A service is an abstract concept implemented on platforms by running the same container image, and configuration, one or more times.

Services communicate with each other through networks. In the Compose Specification, a network is a platform capability abstraction to establish an IP route between containers within services connected together.

Services store and share persistent data into volumes. The Specification describes such a persistent data as a high-level filesystem mount with global options.

Some services require configuration data that is dependent on the runtime or platform. For this, the Specification defines a dedicated configs concept. From inside the container, configs behave like volumes—they’re mounted as files. However, configs are defined differently at the platform level.

A secret is a specific flavor of configuration data for sensitive data that should not be exposed without security considerations. Secrets are made available to services as files mounted into their containers, but the platform-specific resources to provide sensitive data are specific enough to deserve a distinct concept and definition within the Compose Specification.

NoteWith volumes, configs and secrets you can have a simple declaration at the top-level and then add more platform-specific information at the service level.

A project is an individual deployment of an application specification on a platform. A project's name, set with the top-level

name attribute, is used to group

resources together and isolate them from other applications or other installation of the same Compose-specified application with distinct parameters. If you are creating resources on a platform, you must prefix resource names by project and

set the label com.docker.compose.project.

Compose offers a way for you to set a custom project name and override this name, so that the same compose.yaml file can be deployed twice on the same infrastructure, without changes, by just passing a distinct name.

The Compose file

The default path for a Compose file is compose.yaml (preferred) or compose.yml that is placed in the working directory.

Compose also supports docker-compose.yaml and docker-compose.yml for backwards compatibility of earlier versions.

If both files exist, Compose prefers the canonical compose.yaml.

You can use fragments and extensions to keep your Compose file efficient and easy to maintain.

Multiple Compose files can be merged together to define the application model. The combination of YAML files is implemented by appending or overriding YAML elements based on the Compose file order you set. Simple attributes and maps get overridden by the highest order Compose file, lists get merged by appending. Relative paths are resolved based on the first Compose file's parent folder, whenever complimentary files being merged are hosted in other folders. As some Compose file elements can both be expressed as single strings or complex objects, merges apply to the expanded form. For more information, see Working with multiple Compose files.

If you want to reuse other Compose files, or factor out parts of your application model into separate Compose files, you can also use

include. This is useful if your Compose application is dependent on another application which is managed by a different team, or needs to be shared with others.

CLI

The Docker CLI lets you interact with your Docker Compose applications through the docker compose command and its subcommands. If you're using Docker Desktop, the Docker Compose CLI is included by default.

Using the CLI, you can manage the lifecycle of your multi-container applications defined in the compose.yaml file. The CLI commands enable you to start, stop, and configure your applications effortlessly.

Key commands

To start all the services defined in your compose.yaml file:

$ docker compose up

To stop and remove the running services:

$ docker compose down

If you want to monitor the output of your running containers and debug issues, you can view the logs with:

$ docker compose logs

To list all the services along with their current status:

$ docker compose ps

For a full list of all the Compose CLI commands, see the reference documentation.

Illustrative example

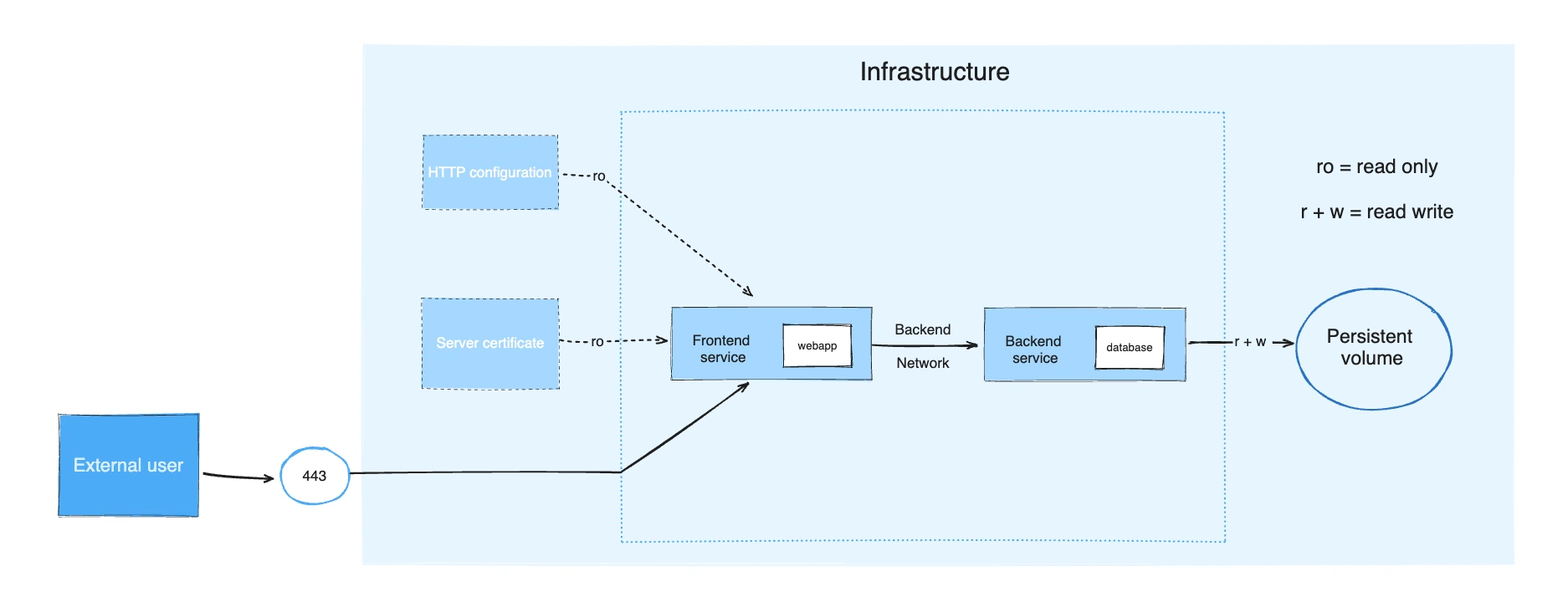

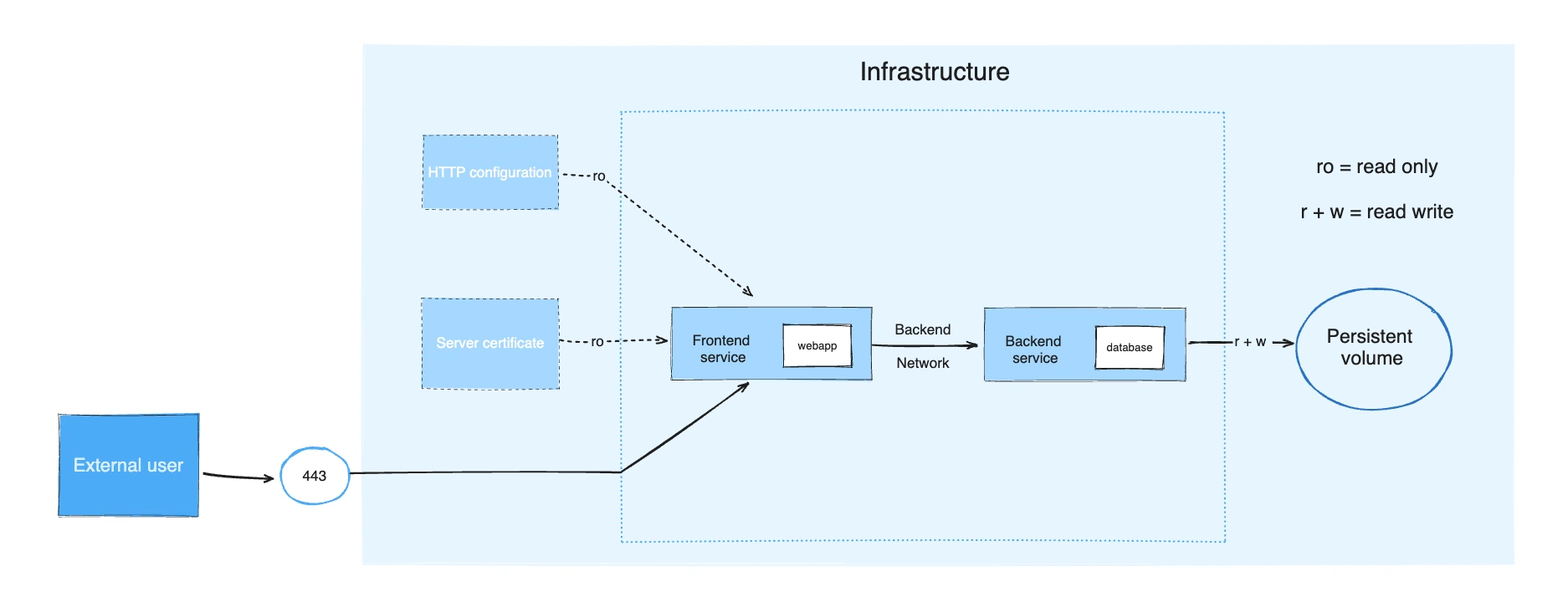

The following example illustrates the Compose concepts outlined above. The example is non-normative.

Consider an application split into a frontend web application and a backend service.

The frontend is configured at runtime with an HTTP configuration file managed by infrastructure, providing an external domain name, and an HTTPS server certificate injected by the platform's secured secret store.

The backend stores data in a persistent volume.

Both services communicate with each other on an isolated back-tier network, while the frontend is also connected to a front-tier network and exposes port 443 for external usage.

The example application is composed of the following parts:

- Two services, backed by Docker images:

webappanddatabase - One secret (HTTPS certificate), injected into the frontend

- One configuration (HTTP), injected into the frontend

- One persistent volume, attached to the backend

- Two networks

services:

frontend:

image: example/webapp

ports:

- "443:8043"

networks:

- front-tier

- back-tier

configs:

- httpd-config

secrets:

- server-certificate

backend:

image: example/database

volumes:

- db-data:/etc/data

networks:

- back-tier

volumes:

db-data:

driver: flocker

driver_opts:

size: "10GiB"

configs:

httpd-config:

external: true

secrets:

server-certificate:

external: true

networks:

# The presence of these objects is sufficient to define them

front-tier: {}

back-tier: {}The docker compose up command starts the frontend and backend services, creates the necessary networks and volumes, and injects the configuration and secret into the frontend service.

docker compose ps provides a snapshot of the current state of your services, making it easy to see which containers are running, their status, and the ports they are using:

$ docker compose ps

NAME IMAGE COMMAND SERVICE CREATED STATUS PORTS

example-frontend-1 example/webapp "nginx -g 'daemon of…" frontend 2 minutes ago Up 2 minutes 0.0.0.0:443->8043/tcp

example-backend-1 example/database "docker-entrypoint.s…" backend 2 minutes ago Up 2 minutes