How services work

To deploy an application image when Docker Engine is in Swarm mode, you create a service. Frequently a service is the image for a microservice within the context of some larger application. Examples of services might include an HTTP server, a database, or any other type of executable program that you wish to run in a distributed environment.

When you create a service, you specify which container image to use and which commands to execute inside running containers. You also define options for the service including:

- The port where the swarm makes the service available outside the swarm

- An overlay network for the service to connect to other services in the swarm

- CPU and memory limits and reservations

- A rolling update policy

- The number of replicas of the image to run in the swarm

Services, tasks, and containers

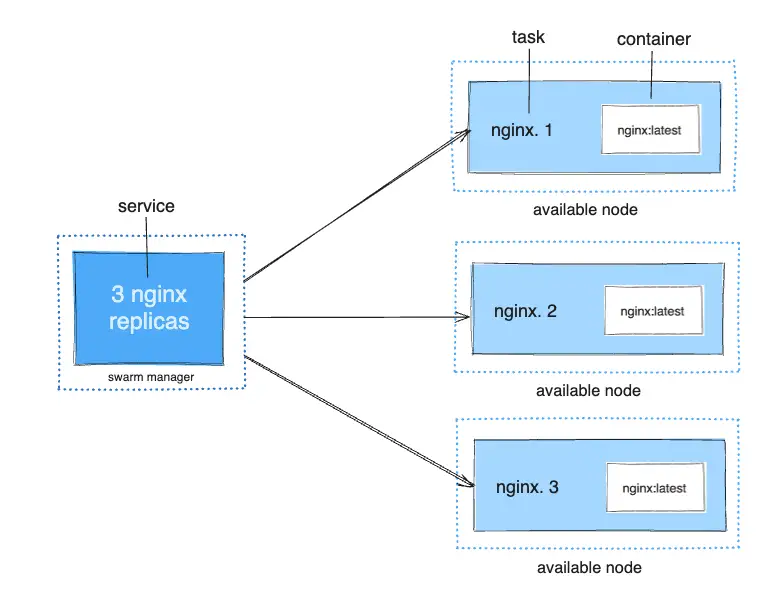

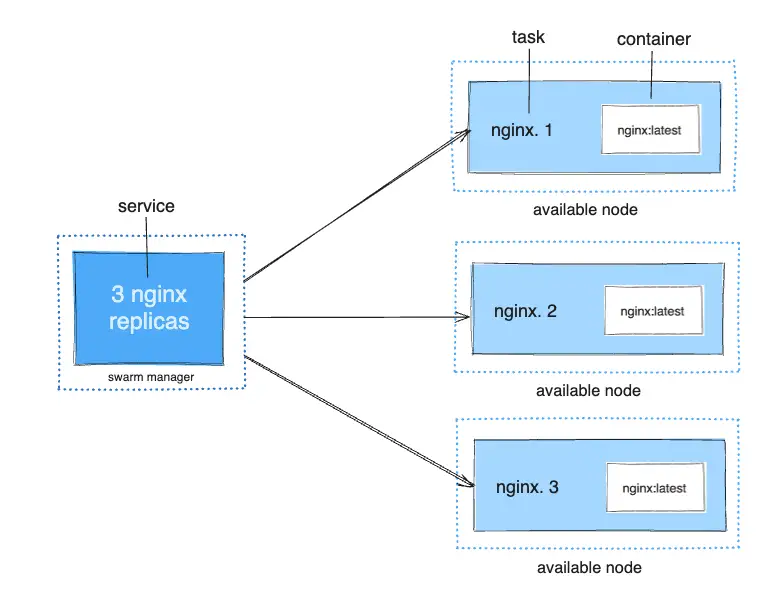

When you deploy the service to the swarm, the swarm manager accepts your service definition as the desired state for the service. Then it schedules the service on nodes in the swarm as one or more replica tasks. The tasks run independently of each other on nodes in the swarm.

For example, imagine you want to load balance between three instances of an HTTP listener. The diagram below shows an HTTP listener service with three replicas. Each of the three instances of the listener is a task in the swarm.

A container is an isolated process. In the Swarm mode model, each task invokes exactly one container. A task is analogous to a “slot” where the scheduler places a container. Once the container is live, the scheduler recognizes that the task is in a running state. If the container fails health checks or terminates, the task terminates.

Tasks and scheduling

A task is the atomic unit of scheduling within a swarm. When you declare a desired service state by creating or updating a service, the orchestrator realizes the desired state by scheduling tasks. For instance, you define a service that instructs the orchestrator to keep three instances of an HTTP listener running at all times. The orchestrator responds by creating three tasks. Each task is a slot that the scheduler fills by spawning a container. The container is the instantiation of the task. If an HTTP listener task subsequently fails its health check or crashes, the orchestrator creates a new replica task that spawns a new container.

A task is a one-directional mechanism. It progresses monotonically through a series of states: assigned, prepared, running, etc. If the task fails, the orchestrator removes the task and its container and then creates a new task to replace it according to the desired state specified by the service.

The underlying logic of Docker's Swarm mode is a general purpose scheduler and orchestrator. The service and task abstractions themselves are unaware of the containers they implement. Hypothetically, you could implement other types of tasks such as virtual machine tasks or non-containerized process tasks. The scheduler and orchestrator are agnostic about the type of the task. However, the current version of Docker only supports container tasks.

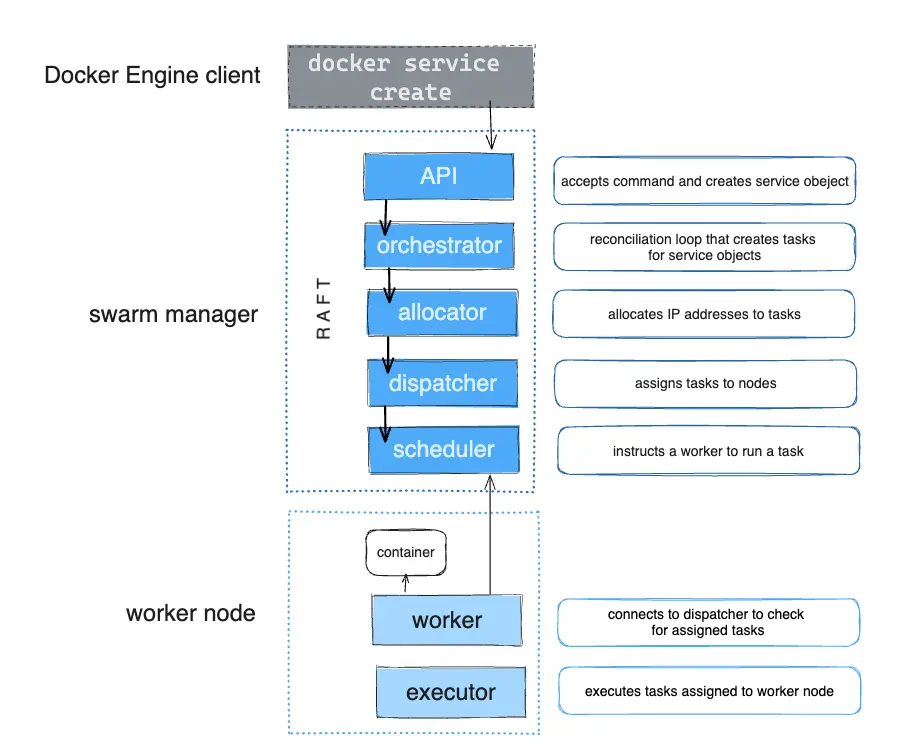

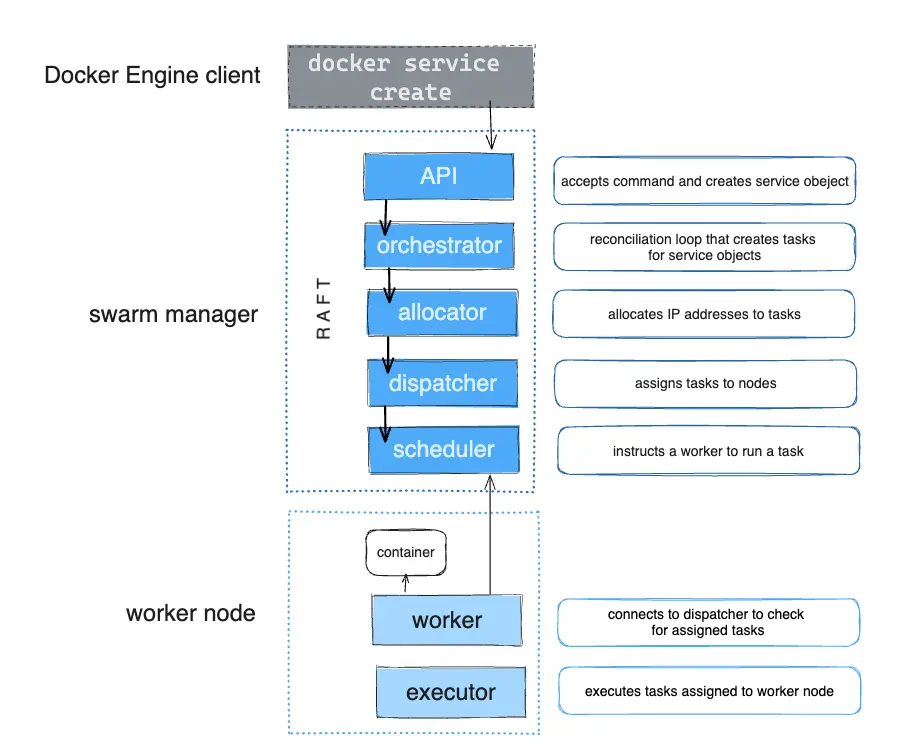

The diagram below shows how Swarm mode accepts service create requests and schedules tasks to worker nodes.

Pending services

A service may be configured in such a way that no node currently in the

swarm can run its tasks. In this case, the service remains in state pending.

Here are a few examples of when a service might remain in state pending.

TipIf your only intention is to prevent a service from being deployed, scale the service to 0 instead of trying to configure it in such a way that it remains in

pending.

If all nodes are paused or drained, and you create a service, it is pending until a node becomes available. In reality, the first node to become available gets all of the tasks, so this is not a good thing to do in a production environment.

You can reserve a specific amount of memory for a service. If no node in the swarm has the required amount of memory, the service remains in a pending state until a node is available which can run its tasks. If you specify a very large value, such as 500 GB, the task stays pending forever, unless you really have a node which can satisfy it.

You can impose placement constraints on the service, and the constraints may not be able to be honored at a given time.

This behavior illustrates that the requirements and configuration of your tasks are not tightly tied to the current state of the swarm. As the administrator of a swarm, you declare the desired state of your swarm, and the manager works with the nodes in the swarm to create that state. You do not need to micro-manage the tasks on the swarm.

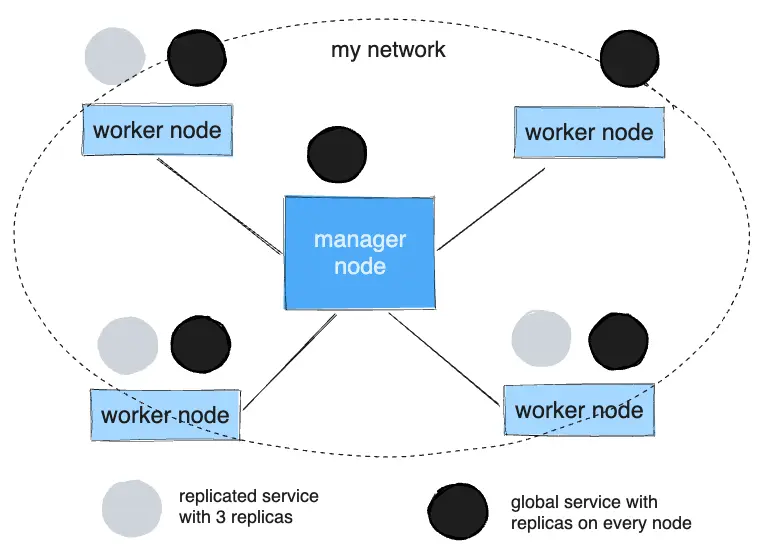

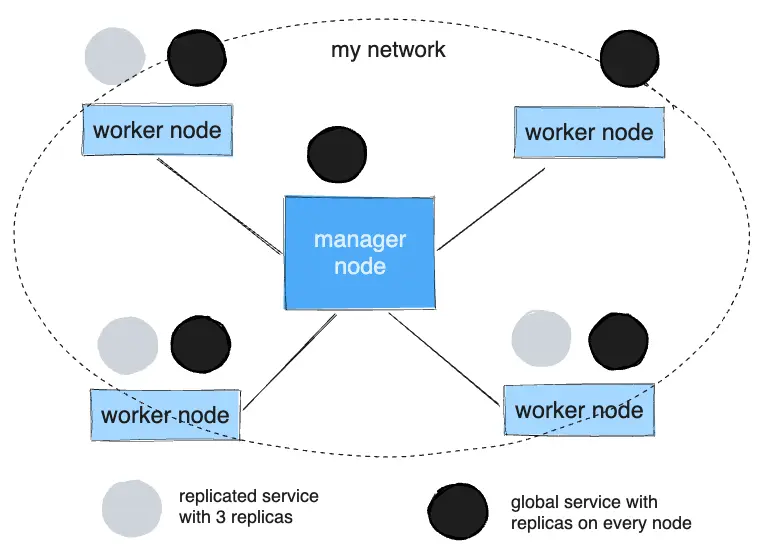

Replicated and global services

There are two types of service deployments, replicated and global.

For a replicated service, you specify the number of identical tasks you want to run. For example, you decide to deploy an HTTP service with three replicas, each serving the same content.

A global service is a service that runs one task on every node. There is no pre-specified number of tasks. Each time you add a node to the swarm, the orchestrator creates a task and the scheduler assigns the task to the new node. Good candidates for global services are monitoring agents, anti-virus scanners or other types of containers that you want to run on every node in the swarm.

The diagram below shows a three-service replica in gray and a global service in black.